Reading this book is like taking the red pill in The Matrix. It’s chock full of “I can’t believe they did that!” and “How do they get away with that?” moments. It’s hard not to feel that the scale of the problem means we’ve already lost. I’ll admit that halfway through I was feeling quite depressed. But of course, giving up is not an option and the second half does propose some ways we can fight back. As Coper himself points out, even peddlers of disinformation justify their claims as facts. “Wake up, read the research, know the science” they say. No one at least is claiming that truth doesn’t matter, it’s evidence that’s the victim here.

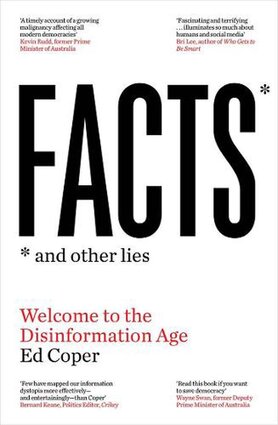

The book begins with histories of both information and disinformation1. The broad sweep of this history will be familiar to most librarians, but it’s full of fascinating details that may not. I had no idea for example that during the 1800 American election campaign, supporters of John Adams maliciously spread a rumour that Thomas Jefferson was dead, which helped them to steal the election. Along the way Coper drops in some interesting ideas, like the ‘Orchestra Pit Principle2’ and ‘Astroturfing3’. He’s particularly good on how media monopolies have destroyed local news, and the devastating effects this has on local democracy and on how psychologists employed by social media companies have learnt to cynically manipulate our behaviour. He’s aware too, that access to information has always been privileged, which only makes the current situation even worse. Coper’s view of truth is nuanced. He recognises that truth has always been contested and that “we need to learn to operate in the jungle of competing realities”. But as he says, “without any commitment to the facts… we lose the whole compass steering this grand human experiment”.

The conclusion seems to be that “our brains are not geared to find truth, but instead to find each other”. It’s our desire for approval and social connection that drives some of us down the rabbit hole, and if we don’t acknowledge that then we’re not going to be able to do much about it. So, the inevitable question is what can we do? Coper starts with what not to do. No negating, myth-busting or labelling please! He suggests that we “pay more attention to giving less attention”. He uses the analogy of infection control.

We should be inoculating people against disinformation and prebunking rather than debunking. Surely there’s a role for libraries here?

In the final section, he gives lots of practical advice, which I urge you to read for yourself. The first step he recommends is to “get your friends to buy this book”. So, in that spirit, and because space doesn’t permit me to do it justice, I’ll leave it for you to discover his strategies for ‘changing minds’, ‘winning the story’, and ‘creating a healthier information ecosystem’. Suffice it to say that reading this as a librarian, I’m sure you will come to the same conclusion as I did that our profession has a lot to offer in finding and providing the solutions.

Coper’s book is written very much from an Australian perspective, with frequent nods across the Pacific to the US. There are occasional uses of Australian slang and New Zealand appears only twice in the index. None of this detracts or distracts from the importance, utility, or enjoyment of the book, which is extremely well written and admirably readable, despite its heavy content. I can’t recommend it highly enough. Go on, take the red pill4!

Rob Cruickshank is a Programming and Learning Specialist at Christchurch City Libraries, and a member of the LIANZA Standing Committee on Freedom of Information.

- Coper distinguishes between misinformation (unintentional), disinformation (deliberate), and malinformation (information may be genuine, but is intended to mislead by removing or changing the context).

- Coper explains this with a quote from Nixon and Reagan media advisor Roger Ailes: “If you have two guys on a stage and one guy says, “I have a solution to the Middle East problem,” and the other guy falls in the orchestra pit, who do you think is going to be on the evening news?”

- Making a false impression of widespread support for a policy, person, or product by using multiple fake online identities.

- For another red pill, check out The Coming Storm, a podcast from the BBC about the conspiracy theories that eventually led to the storming of the US Capitol building, their origins, and how they spread.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed