UNESCO Memory of the World

|

UNESCO is the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. It seeks to build peace through international cooperation in Education, the Sciences and Culture. In this issue of Library Life, we find out more about the Memory of the World Programme. In the next issue, we will feature Dunedin UNESCO City of Literature.

UNESCO established the Memory of the World Programme in 1992. The impetus came originally from a growing awareness of the perilous state of preservation of, and access to, documentary heritage in various parts of the world. War and social upheaval, as well as severe lack of resources, have worsened problems that have existed for centuries. Significant collections worldwide have suffered a variety of fates. Looting and dispersal, illegal trading, destruction, inadequate housing and funding have all played a part. Much as vanished forever; much is endangered. Happily, missing documentary heritage is sometimes rediscovered. |

The vision of the Memory of the World programme is that the world’s documentary heritage belongs to all, should be fully preserved and protected for all and, with due recognition of cultural mores and practicalities, should be permanently accessible to all without hindrance.

The International Memory of the World Register, administered by UNESCO, seeks to identify items of documentary heritage which have worldwide significance. It aims to bring the value and significance of documentary heritage to wider public notice, along with the work performed by libraries, archives and museums in preserving this valuable heritage.

The New Zealand Memory of the World Programme is one of over 60 Memory of the World programmes worldwide. It was established in 2010 by the New Zealand National Commission for UNESCO. The New Zealand Committee’s members have a broad knowledge of New Zealand’s heritage institutions and communities.

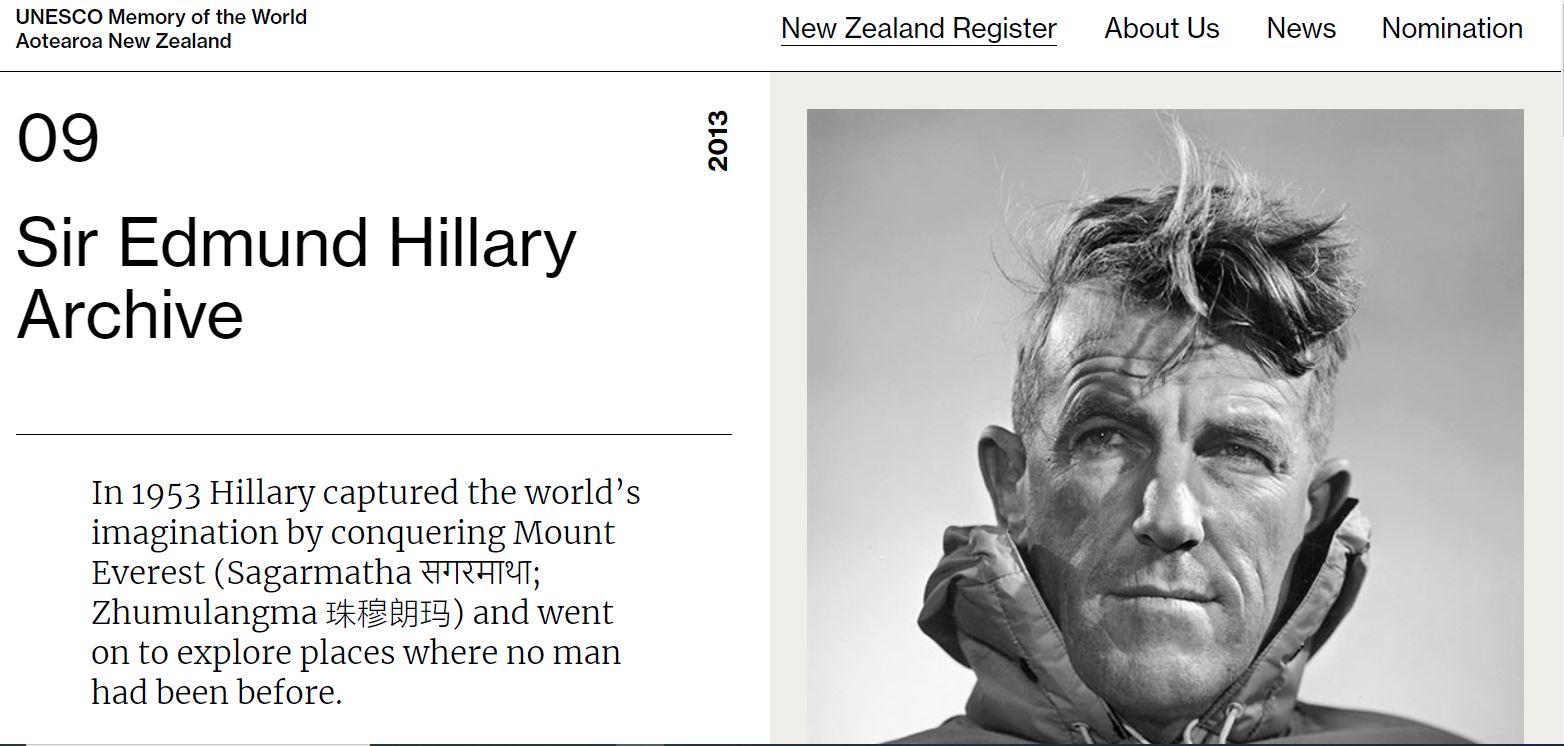

Three of the entries from the New Zealand register have also made it on to the international register: the 1893 Women's Suffrage Petition; The Treaty of Waitangi; and Sir Edmund Hillary Archive, which are all recognised as world heritage. To get these listed on the international register a lengthy nomination was submitted and backed up by referees, and the nomination is considered by an international committee. Helen Clark, former Prime Minister of New Zealand supported the Sir Edmund Hillary Archive nomination. The archive was added to the Memory of the World in 2013 and is held by the Auckland War Memorial Museum.

The Western Pacific Archives at the University of Auckland is on the Asia Pacific register. The research depth of this collection is incredible. The university didn’t have any room to store it so it’s been in off-site storage. It has about 46 different inventories relating to the holdings. In terms of Pacific research, that’s a very important site, and the registration process has helped make people more aware of that and to see the University of Auckland as a research destination for these archives.

The New Zealand Memory of the World Programme operates within the regional framework of MOWCAP, the Memory of the World Committee for Asia/Pacific.

2020 saw five successful nominations added to the New Zealand Memory of the World Register:

The International Memory of the World Register, administered by UNESCO, seeks to identify items of documentary heritage which have worldwide significance. It aims to bring the value and significance of documentary heritage to wider public notice, along with the work performed by libraries, archives and museums in preserving this valuable heritage.

The New Zealand Memory of the World Programme is one of over 60 Memory of the World programmes worldwide. It was established in 2010 by the New Zealand National Commission for UNESCO. The New Zealand Committee’s members have a broad knowledge of New Zealand’s heritage institutions and communities.

Three of the entries from the New Zealand register have also made it on to the international register: the 1893 Women's Suffrage Petition; The Treaty of Waitangi; and Sir Edmund Hillary Archive, which are all recognised as world heritage. To get these listed on the international register a lengthy nomination was submitted and backed up by referees, and the nomination is considered by an international committee. Helen Clark, former Prime Minister of New Zealand supported the Sir Edmund Hillary Archive nomination. The archive was added to the Memory of the World in 2013 and is held by the Auckland War Memorial Museum.

The Western Pacific Archives at the University of Auckland is on the Asia Pacific register. The research depth of this collection is incredible. The university didn’t have any room to store it so it’s been in off-site storage. It has about 46 different inventories relating to the holdings. In terms of Pacific research, that’s a very important site, and the registration process has helped make people more aware of that and to see the University of Auckland as a research destination for these archives.

The New Zealand Memory of the World Programme operates within the regional framework of MOWCAP, the Memory of the World Committee for Asia/Pacific.

2020 saw five successful nominations added to the New Zealand Memory of the World Register:

|

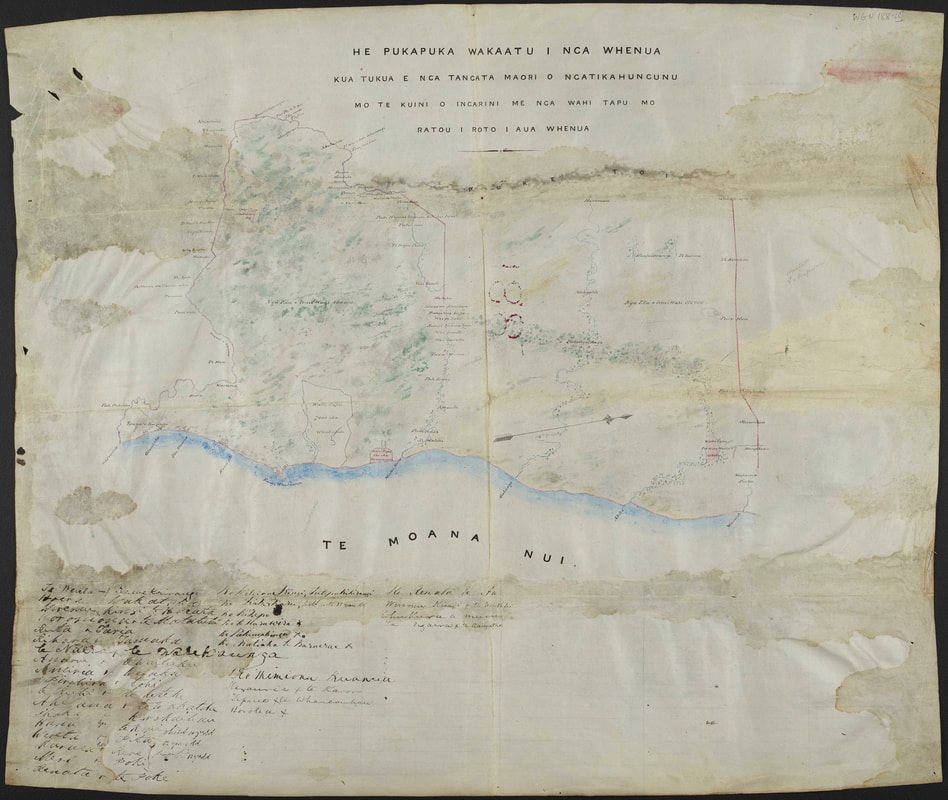

Crown Purchase Deeds, Archives New Zealand, Te Rua Mahara o Te Kāwanatanga Crown Purchase Deeds document the original alienation of Māori land and customary title by the Crown, which by the mid-1860s included two-thirds of Aotearoa New Zealand and virtually the whole of Te Waipounamu, the South Island. As historians, legal scholars and numerous Māori claimants before the Waitangi Tribunal have shown, the early Deeds were Acts of State and more akin to treaties than simple land purchases. Image: Page from the 1853 ‘Castlepoint - Wairarapa’ Deed with a detailed map and te reo Māori headings. ABWN 8102 W5279 Box 42/ WGN 188, Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga. |

|

Robin Hyde literary and personal papers, Alexander Turnbull Library and University of Auckland Library Iris Guiver Wilkinson (1906–1939), better known as Robin Hyde, is widely known in New Zealand as the author of The godwits fly (1938), Passport to Hell (1936), and Nor the years condemn (1938). She was also a poet, journalist, political commentator, war correspondent, editor, mother, feminist and socialist. The Robin Hyde literary and personal papers held by the Alexander Turnbull Library and Special Collections at the University of Auckland illustrate many facets of Hyde’s short but fierce life. Image: Robyn Hyde. Draft Poem. MSS97.1 493a. The University of Auckland. |

|

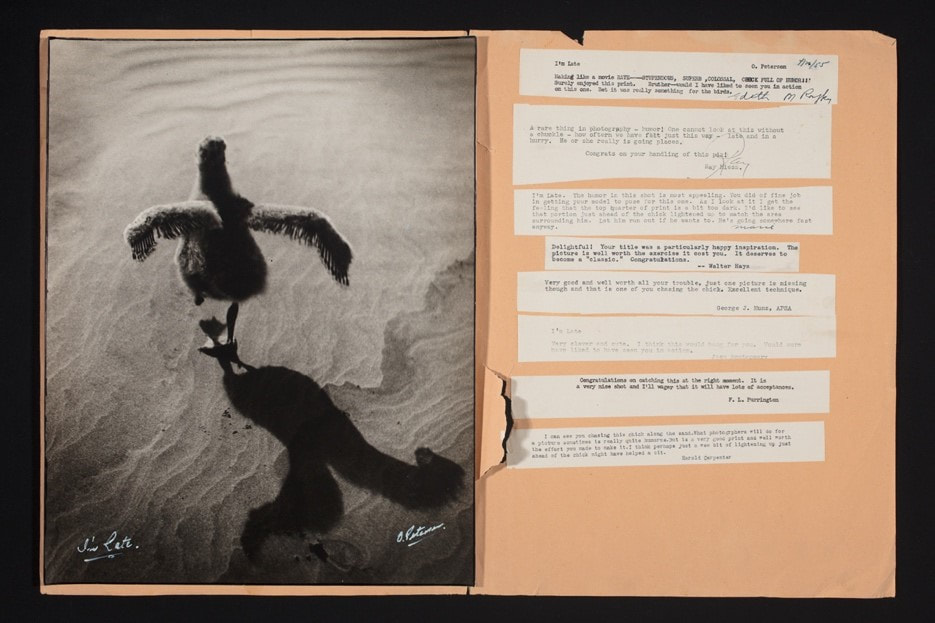

Olaf Petersen Collection, Auckland War Memorial Museum, Tāmaki Paenga Hira Olaf Petersen (1915-1994) is Aotearoa New Zealand’s pre-eminent 20th-century nature photographer. Patient and exacting, Petersen said capturing nature was “being in the right place at the right time”. Image: I’m Late, 1952. Olaf Petersen. Auckland Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira. PH-1988-9. Image reproduced with permission of the Olaf Petersen Estate. |

|

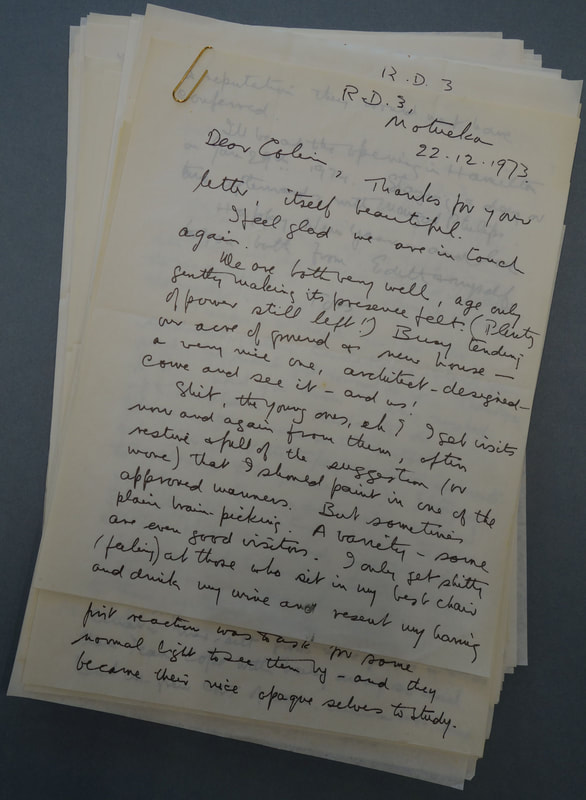

Colin and Anne McCahon: Papers, Hocken Collections Colin and Anne McCahon’s papers document their life and work from 1918 until 1987. The papers, and in particular the letters between friends and family, provide a wonderfully clear picture of their lives, the development of their art and their connections with significant figures in the art world. Image: Letters from Toss and Edith Woollaston to Colin and Anne McCahon. Colin and Anne McCahon Papers, MS-4251/045. Reproduced with permission from the Hocken Collections Uare Taoka o Hākena. |

|

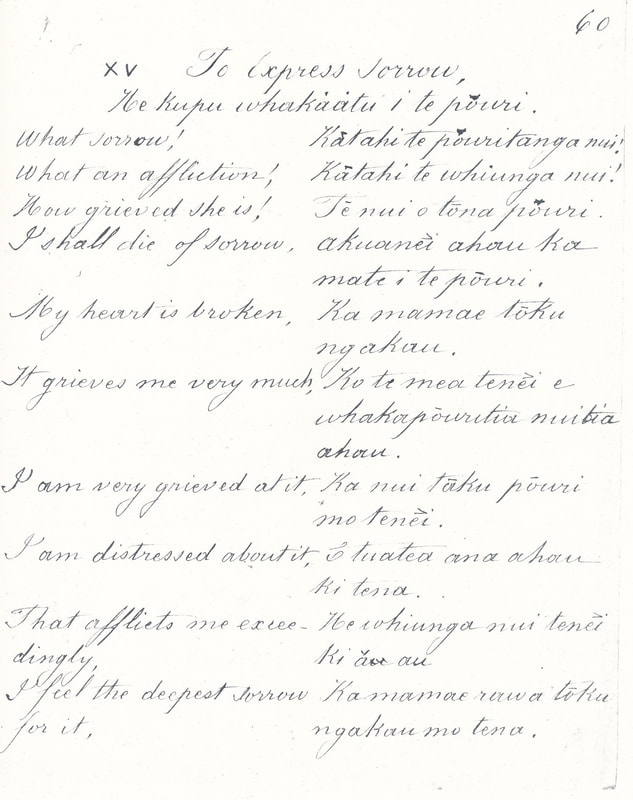

Suzanne Aubert’s ‘Manuscript of Māori Conversation’, Sisters of Compassion Suzanne Aubert came as a missionary in 1860. In her long lifetime as Sister/Mother Mary Joseph, she was a scholar, health innovator, social welfare pioneer, a tireless champion of vulnerable children, advocate for the poor and sick ‘of all creeds and none’, friend to Māori, and founder of the Daughters of Our Lady of Compassion. Unlike previous short, utilitarian phrasebooks, Suzanne Aubert’s work offers wide-ranging communicative phrases, in addition to a grammar summary, a vocabulary section and a lively dramatised English-Māori adaptation of an excerpt from Sir George Grey’s 1854 work on Māori mythology and traditions. Image: Page from Suzanne Aubert’s ‘Manuscript of Māori Conversation’.1969.001.0111. Sisters of Compassion Archives. |

Helen Heath spoke with New Zealand Memory of the World (MoW) committee members David Reeves and Jane Wild about the programme.

David Reeves is the Director of Collections and Research, Auckland Museum. He joined the Museum in January 2011 after a time at the Alexander Turnbull Library as Associate Chief Librarian, Research Access. David’s career also includes roles at the Auckland Art Gallery and at Te Papa managing logistics, storage and documentation of collections. David brings a range of perspectives on the activities of Libraries, Museums, Galleries and Archives, with a particular interest in how they are responding to and utilising the digital environment.

Jane Wild is a documentary heritage specialist, currently working as a Rare Book Curator at Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections. Jane was the Alexander Turnbull Library’s inaugural editor of the ‘National Register of Archives & Manuscripts’, now the Community Archive.

Kia ora and thank you for coming in off the beach to talk with Library Life! I see there are five more successful nominations being added to the New Zealand register and that the nomination round for 2021 has opened. I hope we can encourage more institutions to nominate collections.

So, when does the next EoI close?

March 1, 2021. If people are interested, then they can get their EoI in, and we can give them some assistance with their applications, which are due at the end of May.

Perhaps you could outline for us what it takes for a nomination to be successful?

JW: There are three elements required to be on the register. The New Zealand MoW Committee must be satisfied that the nominated item or items are of outstanding New Zealand significance. That is, there must be demonstrated evidence of historic, aesthetic or community significance; not necessarily all of these, but at least one of them.

The goal is to have significance in a number of areas. At the moment we have just over 40 nominations on the register and there is a sense of the unique qualities that each one has. There are four different factors but they don’t need to present all of them to be considered.

To be selected for registration on the New Zealand Memory of the World Register the documentary heritage should possess the following characteristics:

March 1, 2021. If people are interested, then they can get their EoI in, and we can give them some assistance with their applications, which are due at the end of May.

Perhaps you could outline for us what it takes for a nomination to be successful?

JW: There are three elements required to be on the register. The New Zealand MoW Committee must be satisfied that the nominated item or items are of outstanding New Zealand significance. That is, there must be demonstrated evidence of historic, aesthetic or community significance; not necessarily all of these, but at least one of them.

The goal is to have significance in a number of areas. At the moment we have just over 40 nominations on the register and there is a sense of the unique qualities that each one has. There are four different factors but they don’t need to present all of them to be considered.

To be selected for registration on the New Zealand Memory of the World Register the documentary heritage should possess the following characteristics:

DR: This is where the EoI process is really helpful, because we are able to work with organisations, or the holders of these collections to help them focus their nominations. Some people, reading the information on the website assume that they don’t qualify because they don’t tick all five boxes. However, having strength in two out of the five is enough, perhaps with some strength in the others.

The other thing that we’ve helped people to clarify through the EoI is the focus or purpose. We can look at the Sir Edmund Hillary archive as an example (which is now on the international register as well). Through the whole process we had to be clear that we were not celebrating Sir Ed and his achievements, we were celebrating what the archive told us about his life and the world of philanthropy and exploration and so forth. So, it’s the importance of the material and how it elucidates our understanding of his work – not the fact that he climbed Mount Everest. The MoW programme is designed to promote the value of keeping objects and documents that tell us about our history, so the things that end up on the register need to have strength as archives, almost irrespective of what the subject matter is. Clearly, the subject matter is important because that’s the hook for people to be interested but the importance of it as an information source is something that will illustrate the history of humanity broadly speaking.

The other thing that we’ve helped people to clarify through the EoI is the focus or purpose. We can look at the Sir Edmund Hillary archive as an example (which is now on the international register as well). Through the whole process we had to be clear that we were not celebrating Sir Ed and his achievements, we were celebrating what the archive told us about his life and the world of philanthropy and exploration and so forth. So, it’s the importance of the material and how it elucidates our understanding of his work – not the fact that he climbed Mount Everest. The MoW programme is designed to promote the value of keeping objects and documents that tell us about our history, so the things that end up on the register need to have strength as archives, almost irrespective of what the subject matter is. Clearly, the subject matter is important because that’s the hook for people to be interested but the importance of it as an information source is something that will illustrate the history of humanity broadly speaking.

- 1. Has demonstrable historic, aesthetic or cultural significance to a community or the nation

- 2. Be unique and irreplaceable

- 3. Is a primary or significant source that documents a historical or cultural event that has had a lasting impact and influenced the course of New Zealand history

- 4. Be an outstanding example of a document or an experience

-

JW: It can give a new depth too. The Colin and Anne McCahon papers at the Hocken Collections is one of the successful nominations for this round and it focuses on the in-depth correspondence that’s gone on through the years that helped form his life work but actually gives an insight into Colin and Anne in terms of relationships with family, and with friends. The infrastructure of that deep archive means that when people are trying to learn a little more about Colin McCahon as an artist this archive will be a real highlight for researchers.

It’s a great opportunity for institutions like the Hocken. We’ve just had a blog post about Muriel Bell at the Auckland Libraries to do with our food exhibition. The Dr Muriel Bell Papers were a successful nomination to the register last year – she was a pioneering nutritionist. It’s about putting people on the map of cultural collections that are in New Zealand and making people aware of where you can go for that in-depth information. David has mentioned the Sir Edmund Hillary archive at the Auckland War Memorial Museum, another new addition to the register from there is the Olaf Petersen Collection of photographs, he’s not a photographer that everyone knows about but that collection offers real insight into his particular eye and his documentation into quite a specific area in the West alongside his wider work. We have a number of photographic collections, this one being added means people will recognise his skill as a photographer where he was not a name that people knew about before.

It’s a great opportunity for institutions like the Hocken. We’ve just had a blog post about Muriel Bell at the Auckland Libraries to do with our food exhibition. The Dr Muriel Bell Papers were a successful nomination to the register last year – she was a pioneering nutritionist. It’s about putting people on the map of cultural collections that are in New Zealand and making people aware of where you can go for that in-depth information. David has mentioned the Sir Edmund Hillary archive at the Auckland War Memorial Museum, another new addition to the register from there is the Olaf Petersen Collection of photographs, he’s not a photographer that everyone knows about but that collection offers real insight into his particular eye and his documentation into quite a specific area in the West alongside his wider work. We have a number of photographic collections, this one being added means people will recognise his skill as a photographer where he was not a name that people knew about before.

DR: There’s a symbiotic thing in play, New Zealand doesn’t have a huge infrastructure for making people famous, so in some ways this register is part of bringing things out of the shadows, bringing things to light. Something may have national significance but, by putting it on the register, it gains even further significance because more people get to know about it. So in the case of the Olaf Petersen collection, most people will not have heard of him at all but he was a very important early conservationist and natural scientist, documenting natural environments. His concern about the degradation of these environments through the 1930s to 1960s was way ahead of contemporary concerns for those issues, such as Kauri dieback in the Waitakere ranges, he was documenting the state of those forests two generations ago. His place on the register will help build his reputation.

Overall, the register builds New Zealand’s sense that it does have a culture, things to be proud of and to learn about ourselves.

It’s interesting, looking around the world, different countries use this programme in different ways. In some countries, we’ve seen it’s an intensely political thing. New Zealand’s way is a bit more low key but we’ve got an opportunity to really celebrate what we’ve got. The companion programme to ours is the UNESCO World Heritage sites, New Zealand has a relatively low number of those as well. So, where they are landscapes, buildings and monuments of importance; this is the moveable cultural property companion to that.

Overall, the register builds New Zealand’s sense that it does have a culture, things to be proud of and to learn about ourselves.

It’s interesting, looking around the world, different countries use this programme in different ways. In some countries, we’ve seen it’s an intensely political thing. New Zealand’s way is a bit more low key but we’ve got an opportunity to really celebrate what we’ve got. The companion programme to ours is the UNESCO World Heritage sites, New Zealand has a relatively low number of those as well. So, where they are landscapes, buildings and monuments of importance; this is the moveable cultural property companion to that.

You’ve spoken a little already about the nomination process, would you like to expand on that?

DR: Working with people through the EoI process is really helpful because we can talk through the kinds of referees who can corroborate - because it’s not just that holds the collection saying how great it is - referees provide evidence of how an academic or writer - somebody has used the collection and what benefit it has had. That’s another benefit of the programme - it’s an opportunity to celebrate and promote the use of archives and how they contribute to wider understanding. So, if there are key people in the community who have made use of the archive and can talk about education programmes that have come through it or publications that have flowed from it that’s really helpful.

JW: Along with that, people are very focussed on what is in their own collections and we are able to point them to other collections that have compatible material. So we are starting to see more joint nominations. For example, in this latest round, we have Robin Hyde’s literary and personal papers at both Alexander Turnbull Library and University of Auckland Library special collections. The provenance for that collection was the same. It raises awareness - in that research pathway, you may need to go to a number of places to really explore your research topic or subject.

The other game-changer has been the digitisation of some of that content. When there have been some key digitisation programmes we can make sure that the content is linked to our website so people can find it. We are hoping that will grow a lot more, particularly with the 2022 school history syllabus requirements. The hyper-local idea about students researching places that are close to them - they’ll also be able to find out the significance of those places and many of them will be represented by nominations in the register. We have developed a hyperlinked tile for each inscription to take the researcher to the website.

DR: Working with people through the EoI process is really helpful because we can talk through the kinds of referees who can corroborate - because it’s not just that holds the collection saying how great it is - referees provide evidence of how an academic or writer - somebody has used the collection and what benefit it has had. That’s another benefit of the programme - it’s an opportunity to celebrate and promote the use of archives and how they contribute to wider understanding. So, if there are key people in the community who have made use of the archive and can talk about education programmes that have come through it or publications that have flowed from it that’s really helpful.

JW: Along with that, people are very focussed on what is in their own collections and we are able to point them to other collections that have compatible material. So we are starting to see more joint nominations. For example, in this latest round, we have Robin Hyde’s literary and personal papers at both Alexander Turnbull Library and University of Auckland Library special collections. The provenance for that collection was the same. It raises awareness - in that research pathway, you may need to go to a number of places to really explore your research topic or subject.

The other game-changer has been the digitisation of some of that content. When there have been some key digitisation programmes we can make sure that the content is linked to our website so people can find it. We are hoping that will grow a lot more, particularly with the 2022 school history syllabus requirements. The hyper-local idea about students researching places that are close to them - they’ll also be able to find out the significance of those places and many of them will be represented by nominations in the register. We have developed a hyperlinked tile for each inscription to take the researcher to the website.

Is it just for larger institutions or can people nominate collections from smaller organisations? I guess what you were saying earlier about collaborative nominations is applicable here?

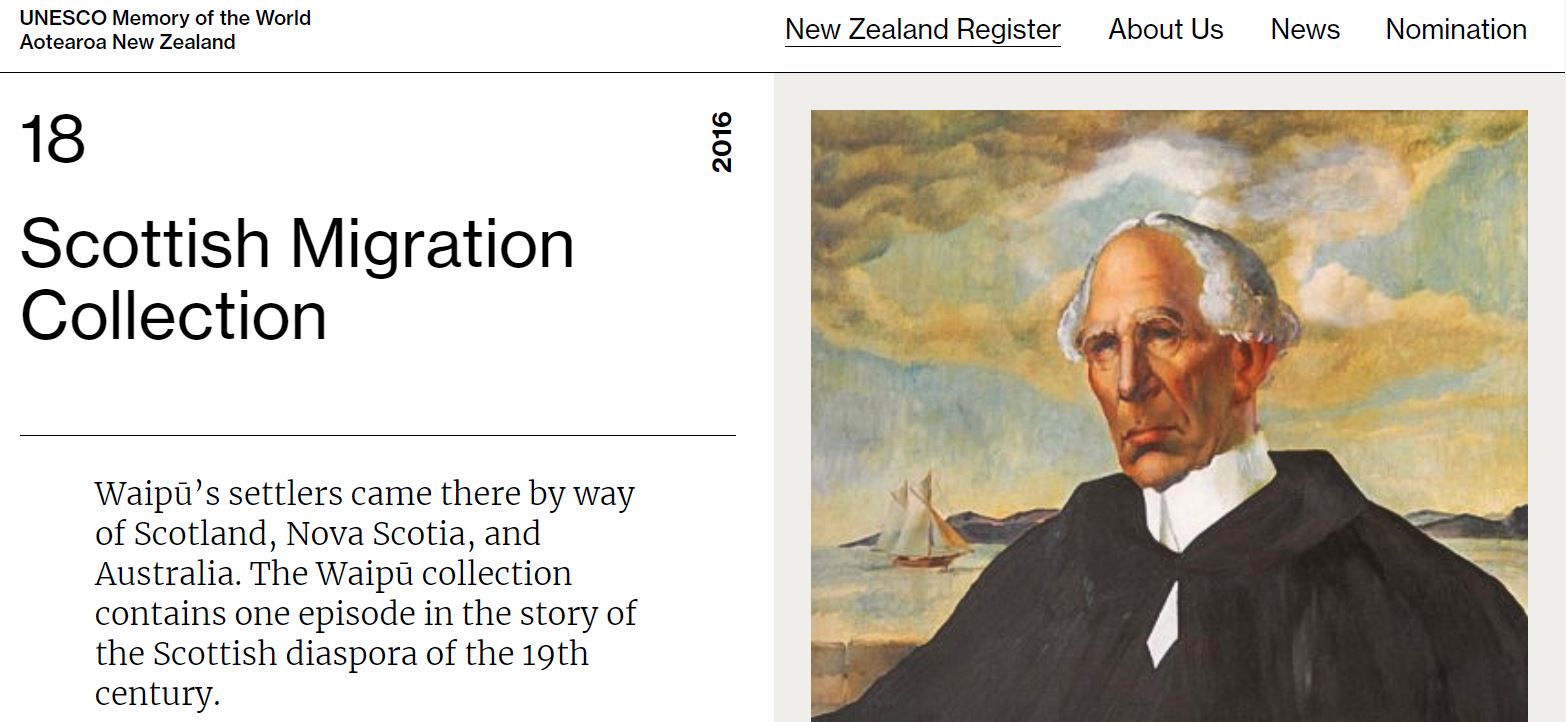

JW: Yes, well one that springs to mind is the Waipu Scottish Migration Collection – it’s a very small community organisation, which has papers relating to the immigration to New Zealand and the community at Waipu. We are getting a lot of smaller museums and historical societies interested at the moment and those are groups that the EoI process can specifically support to develop their proposal. One this year is Suzanne Aubert’s ‘Original Manuscript of Māori Conversation & Grammar’, which was nominated by the Sisters of Compassion – so that’s a religious archive. We were really pleased to see this community archive, based in Island Bay, successful with their nomination. We are pleased to see nominations from not just the big institutions. At the same time, those big institutions do have a lot of taonga that we do want to see listed as well.

DR: Also, that capacity – staff time to put into doing some research and assembling the material for a nomination. That’s something, through this EoI process, that we are keen to provide assistance where we can to smaller organisations to perhaps pair them up with somebody who has written a successful nomination in the past – recognising that it may be a lone, part-time archivist who may feel daunted by the whole process.

JW: Yes, well one that springs to mind is the Waipu Scottish Migration Collection – it’s a very small community organisation, which has papers relating to the immigration to New Zealand and the community at Waipu. We are getting a lot of smaller museums and historical societies interested at the moment and those are groups that the EoI process can specifically support to develop their proposal. One this year is Suzanne Aubert’s ‘Original Manuscript of Māori Conversation & Grammar’, which was nominated by the Sisters of Compassion – so that’s a religious archive. We were really pleased to see this community archive, based in Island Bay, successful with their nomination. We are pleased to see nominations from not just the big institutions. At the same time, those big institutions do have a lot of taonga that we do want to see listed as well.

DR: Also, that capacity – staff time to put into doing some research and assembling the material for a nomination. That’s something, through this EoI process, that we are keen to provide assistance where we can to smaller organisations to perhaps pair them up with somebody who has written a successful nomination in the past – recognising that it may be a lone, part-time archivist who may feel daunted by the whole process.

Are there any areas in particular that you’d like to see grow?

DR: This is something we have conversations about now and then. A couple of years ago, we identified that the register was a bit thin on scientific papers, the study of science in New Zealand and archives that support early scientific endeavours. That’s an area we could probably still grow more.

JW: Also, papers of women is another area. Muriel Bell, for example, might not have been well known but was probably a superstar in her own way in terms of nutrition in New Zealand. Diverse communities as well. The UNESCO programme has done a lot with collecting for COVID-19 over the last year or so. It’s about getting the recognition of the documentary heritage that impacts everyone and the responsibility to share the stories. It was great to see the recent story in Library Life about the documentation surrounding Turnbull’s COVID collecting and the wider COVID collecting across Aotearoa. I’m guessing that there will be more deliberate attempts to get those stories of the “every person”, not necessarily the famous people but what it is to be living in the current moment. So, that’s one of our challenges – looking at ways to support that kind of collecting.

DR: There is a bit of tension between people understanding something being of national significance but also still having only local content. One example I can think of is Auckland Libraries’ J T Diamond collection of West Auckland material. It is an extraordinary deep collection from one locality. We had a bit of a debate around whether it held national significance. What tipped it over to a yes was the nature of the collecting, the nature of the documentation, the thoroughness of it was of national significance. Even though the subject matter didn’t span the entire country. It was such a thorough archive and an incredibly important resource to promote and celebrate that it deserved its place on the register.

JW: Yes, and Diamond wasn’t a professional anthropologist but he did have links with people at the museum and other places. He was really a self-taught enthusiast but he made it his life’s work to document the area. Thinking about local – Māori language and sites of significance are incredibly important. The addition of the Crown Purchase Deeds nominated by Archives NZ will add another 6,300 deeds across Aotearoa to the register this year. This is a large collection at over 22 linear metres. Contrast this with just one slate with a waiata which went into the register - it was crucially important because of what was known about it up in Kerikeri. So, in terms of the incredible knowledge that lies in documentary heritage, in terms of understanding Aotearoa, Māori content is very important. You’ll see that in a number of the nominations so far. The first printed book in Māori is one. Normally, print isn’t covered in documentary heritage because it tends not to be unique but this is the only known copy of the 1817 book at the museum.

DR: This is something we have conversations about now and then. A couple of years ago, we identified that the register was a bit thin on scientific papers, the study of science in New Zealand and archives that support early scientific endeavours. That’s an area we could probably still grow more.

JW: Also, papers of women is another area. Muriel Bell, for example, might not have been well known but was probably a superstar in her own way in terms of nutrition in New Zealand. Diverse communities as well. The UNESCO programme has done a lot with collecting for COVID-19 over the last year or so. It’s about getting the recognition of the documentary heritage that impacts everyone and the responsibility to share the stories. It was great to see the recent story in Library Life about the documentation surrounding Turnbull’s COVID collecting and the wider COVID collecting across Aotearoa. I’m guessing that there will be more deliberate attempts to get those stories of the “every person”, not necessarily the famous people but what it is to be living in the current moment. So, that’s one of our challenges – looking at ways to support that kind of collecting.

DR: There is a bit of tension between people understanding something being of national significance but also still having only local content. One example I can think of is Auckland Libraries’ J T Diamond collection of West Auckland material. It is an extraordinary deep collection from one locality. We had a bit of a debate around whether it held national significance. What tipped it over to a yes was the nature of the collecting, the nature of the documentation, the thoroughness of it was of national significance. Even though the subject matter didn’t span the entire country. It was such a thorough archive and an incredibly important resource to promote and celebrate that it deserved its place on the register.

JW: Yes, and Diamond wasn’t a professional anthropologist but he did have links with people at the museum and other places. He was really a self-taught enthusiast but he made it his life’s work to document the area. Thinking about local – Māori language and sites of significance are incredibly important. The addition of the Crown Purchase Deeds nominated by Archives NZ will add another 6,300 deeds across Aotearoa to the register this year. This is a large collection at over 22 linear metres. Contrast this with just one slate with a waiata which went into the register - it was crucially important because of what was known about it up in Kerikeri. So, in terms of the incredible knowledge that lies in documentary heritage, in terms of understanding Aotearoa, Māori content is very important. You’ll see that in a number of the nominations so far. The first printed book in Māori is one. Normally, print isn’t covered in documentary heritage because it tends not to be unique but this is the only known copy of the 1817 book at the museum.

What are your hopes for the future of the Memory of the World Programme in New Zealand?

DR: It would be great if it was as well known as the World Heritage sites programme. We’d like to see more promotion highlighting the value of archives, the organisations and the people that care for them and provide access to them. The register could be almost like a hall of fame, which then confers general interest across the sector, so interest is raised even for things that are not on the register, which raises the value of collecting, looking after collections and providing access to collections in local environments. Whether that’s a local church archive, sports archive or school archive, for example, there’s a general elevation of valuing that work. We hope that local librarians will be able to use the register to advocate for their archives to demonstrate this aspect of their work is valued and has a legacy. To demonstrate to their funders that value can be based on more than a purely transactional account of how many people came in the door or how many books were loaned this week.

JW: It becomes the tip of the documentary heritage iceberg, underneath is all the other documentary heritage. One of the lovely things around the documentary heritage formats is the level of oral history we’ve got in there. Hearing people’s voices is so important. Turnbull has some recordings of Cambodian refugees, for instance. Nga Taonga Sound & Vision have nominated the World War II Mobile Broadcasting Unit recordings, which are so poignant and moving. For some people, they are the only opportunity to hear a loved family member. What I’d love to see more is younger people connecting more with that content through hearing. Hopefully, we’ll be doing some more video work so we can get some of our experts sharing that content and talking about it in short clips that can activate interest.

DR: Often the holding organisations are subsidiaries of larger organisations, who provide funding and resources. Something being on the register can raise the profile of the smaller organisations and can perhaps allow additional resources or time or interest to be afforded.

JW: Yes, because these collections need long term preservation. You don’t want to receive a nomination and then lose your air conditioning or security. You’ve got a commitment to keeping something safe and accessible.

DR: So if an organisation was putting in a funding application they could cite their collections on the register to prove the importance of the funding needed, not just for the physical storage requirements but also digitisation programmes to make the material more accessible.

Librarians are often the first port of call in helping people with research, whether it is family history research or school students fulfilling their studies librarians can point people to this register and that can, in turn, lead people to discover other collections these organisations hold. It’s also a great tool for librarians to discover more themselves about holdings that are out there.

Thanks so much for talking with us. We can’t wait to see what the future holds for the register.

DR: It would be great if it was as well known as the World Heritage sites programme. We’d like to see more promotion highlighting the value of archives, the organisations and the people that care for them and provide access to them. The register could be almost like a hall of fame, which then confers general interest across the sector, so interest is raised even for things that are not on the register, which raises the value of collecting, looking after collections and providing access to collections in local environments. Whether that’s a local church archive, sports archive or school archive, for example, there’s a general elevation of valuing that work. We hope that local librarians will be able to use the register to advocate for their archives to demonstrate this aspect of their work is valued and has a legacy. To demonstrate to their funders that value can be based on more than a purely transactional account of how many people came in the door or how many books were loaned this week.

JW: It becomes the tip of the documentary heritage iceberg, underneath is all the other documentary heritage. One of the lovely things around the documentary heritage formats is the level of oral history we’ve got in there. Hearing people’s voices is so important. Turnbull has some recordings of Cambodian refugees, for instance. Nga Taonga Sound & Vision have nominated the World War II Mobile Broadcasting Unit recordings, which are so poignant and moving. For some people, they are the only opportunity to hear a loved family member. What I’d love to see more is younger people connecting more with that content through hearing. Hopefully, we’ll be doing some more video work so we can get some of our experts sharing that content and talking about it in short clips that can activate interest.

DR: Often the holding organisations are subsidiaries of larger organisations, who provide funding and resources. Something being on the register can raise the profile of the smaller organisations and can perhaps allow additional resources or time or interest to be afforded.

JW: Yes, because these collections need long term preservation. You don’t want to receive a nomination and then lose your air conditioning or security. You’ve got a commitment to keeping something safe and accessible.

DR: So if an organisation was putting in a funding application they could cite their collections on the register to prove the importance of the funding needed, not just for the physical storage requirements but also digitisation programmes to make the material more accessible.

Librarians are often the first port of call in helping people with research, whether it is family history research or school students fulfilling their studies librarians can point people to this register and that can, in turn, lead people to discover other collections these organisations hold. It’s also a great tool for librarians to discover more themselves about holdings that are out there.

Thanks so much for talking with us. We can’t wait to see what the future holds for the register.