Review of the Public Lending Right Scheme

|

A review of the Public Lending Right (PLR) for New Zealand Authors started in March 2020 and the report on the review from the National Library was released at the end of July 2020. LIANZA’s rep on the PLR Advisory Group is Glen Walker, a former LIANZA president and current head of Library & Information Services at Lincoln University.

One of the issues that arose from the report was that more than half of librarian respondents to the survey were not very familiar with how the PLR works. In this feature we outline the PLR, the findings of the review; and talk with Alison McIntyre, Principal Advisor in the Office of the National Librarian, about the review and the role libraries play in the scheme. What is the Public Lending Right scheme? The Public Lending Right for New Zealand Authors scheme (PLR) was established in 2008, replacing the New Zealand Authors’ Fund established in 1973. The PLR provides payments for New Zealand authors, in recognition that their books are available for use in New Zealand libraries. The PLR annual fund of $2.4 million is divided among registered authors, based on how many copies of their works are held by libraries and if they meet the eligibility requirements of the Act. |

The PLR is administered by the National Library under the Public Lending Right for New Zealand Authors Act 2008 (the Act) and associated regulations. The National Library is part of the Department of Internal Affairs. (Source)

The recent Budget 2020 announcement of a major funding package for libraries includes a 20% increase to the Public Lending Right fund. The $1.6 million extra over four years is the first increase to the fund since 2008.

Why was the review done?

A Department of Internal Affairs’ regulatory review in 2019 identified a need for improvement in multiple areas of the Public Lending Right scheme. The findings of the regulatory review have been endorsed by the PLR Advisory Group. The New Zealand Society of Authors (NZSA) has also publicly lobbied for improvements to the PLR. (Source)

What was reviewed?

The review looked at the PLR’s policy intent, funding, regulations, scope, and operational procedures. As part of looking at PLR’s scope, the current exclusion of e-books, audiobooks and school libraries, and the impact of the Marrakesh Treaty was considered. (Source)

Read the terms of reference for the review (pdf, 245KB)

What has happened to date?

During March and April 2020, sector stakeholders and individuals who had previously registered for the PLR scheme were contacted to participate in online surveys. Over 540 responses were received from individual respondents including authors, illustrators, editors, librarians and publishers. Key stakeholders from across the sector also responded to the professional bodies online survey.

Consultants worked closely with the NZSA, New Zealand libraries and conducted interviews with other key stakeholders across the sector to ask them about their experience of the PLR. This was to gain a better understanding of how the PLR operates in practice, the key issues of the scheme and identify opportunities for change.

An issues paper has been produced that presents the results of a targeted consultation with key stakeholders about issues associated with New Zealand’s PLR scheme, its policy intent, regulations, design, and administration. The paper also provides some initial signals towards developing future options for the PLR scheme’s enhancement. (Source)

LIANZA’s rep on the Advisory Group, Glen Walker told LIANZA Office,

The recent Budget 2020 announcement of a major funding package for libraries includes a 20% increase to the Public Lending Right fund. The $1.6 million extra over four years is the first increase to the fund since 2008.

Why was the review done?

A Department of Internal Affairs’ regulatory review in 2019 identified a need for improvement in multiple areas of the Public Lending Right scheme. The findings of the regulatory review have been endorsed by the PLR Advisory Group. The New Zealand Society of Authors (NZSA) has also publicly lobbied for improvements to the PLR. (Source)

What was reviewed?

The review looked at the PLR’s policy intent, funding, regulations, scope, and operational procedures. As part of looking at PLR’s scope, the current exclusion of e-books, audiobooks and school libraries, and the impact of the Marrakesh Treaty was considered. (Source)

Read the terms of reference for the review (pdf, 245KB)

What has happened to date?

During March and April 2020, sector stakeholders and individuals who had previously registered for the PLR scheme were contacted to participate in online surveys. Over 540 responses were received from individual respondents including authors, illustrators, editors, librarians and publishers. Key stakeholders from across the sector also responded to the professional bodies online survey.

Consultants worked closely with the NZSA, New Zealand libraries and conducted interviews with other key stakeholders across the sector to ask them about their experience of the PLR. This was to gain a better understanding of how the PLR operates in practice, the key issues of the scheme and identify opportunities for change.

An issues paper has been produced that presents the results of a targeted consultation with key stakeholders about issues associated with New Zealand’s PLR scheme, its policy intent, regulations, design, and administration. The paper also provides some initial signals towards developing future options for the PLR scheme’s enhancement. (Source)

LIANZA’s rep on the Advisory Group, Glen Walker told LIANZA Office,

‘The input of a LIANZA representative can be useful for explaining the nuances of library operation to other members of the advisory group and interested parties like those who ran the recent survey. I explained that, from a library point of view, there are a number of complicating factors limiting what can be achieved with reporting. For example, libraries do not all use the same systems or even a consistent source or standard of cataloguing records. So, an instant report on the numbers of Book X is not possible. Also, some libraries will not have noted whether an author is a New Zealander or not – so such a report may not be possible at all. Additionally, we have many models in play with regard to e-books and e-audio – from outright ownership through to licensing a group of titles for a period or having some form of rent-to-own. |

We have extracted parts of the issues paper in this special report below and asked some follow-up questions of Alison McIntyre, Principal Advisor in the Office of the National Librarian . You can read the full report here (pdf, 2.5MB).

Scott, C., & Hartley, A. (2020). Review of the Public Lending Right Scheme Issues Paper; Allen + Clarke

Scott, C., & Hartley, A. (2020). Review of the Public Lending Right Scheme Issues Paper; Allen + Clarke

Extracts from the Review of the Public Lending Right

With only a few exceptions, the majority of [survey] participants ranked the most important outcome of the PLR scheme as being to compensate New Zealand authors for their works being made available to readers free of charge. They also emphasised the need for the PLR scheme’s funding pool to be increased after remaining static for twelve years.

Numerous commentaries were provided on problems that stakeholders have encountered in their interaction with the PLR scheme’s regulations, in particular with the registration process and the way eligible titles are surveyed in New Zealand libraries. The rise of e-books in particular is shown to have implications for the survey methodology currently used for determining eligible library holdings, given that these formats are not included in the survey’s scope nor ‘held’ in the conventional sense (i.e. in a similar way to print-media). E-books are one of a range of technological changes that have occurred in the PLR scheme’s operating environment since it was established in 2008. These include sophisticated digital library and collection management systems, copyright licensing, and e-publishing. Stakeholders emphasised the urgent need to modernise the PLR scheme’s regulations and administration to keep up with these developments and expressed a view that existing collection management software in New Zealand could accurately process holding (and lending) data and automatically calculate PLR scheme payments. An automated system would also reduce administration costs in the long-term.

Stakeholders observed in this context that copyright exceptions under the Marrakesh Treaty relate for the most part to the creation of accessible format copies of a given title that are, for the most part, also digital products. A need was identified to consider the distinction between arrangements that relate to the licensing of digital formats, and the inclusion of digital formats (e.g. digital accessible format copies) of eligible titles in the PLR scheme.

As a first step towards improving the PLR scheme, it has been suggested that New Zealand libraries, their collections and IT managers, copyright licensing organisations, statisticians, and other leading stakeholder organisations combine forces and share their expertise to modernise and streamline how the PLR scheme can achieve desired policy outcomes and best serve New Zealand authors. A revision of the PLR’s governing legislation and regulations may be necessary to deliver to the PLR’s policy intent and keep up with the digital technologies which now define the PLR scheme’s operating environment (Scott & Hartley, 2020, p.1).

Numerous commentaries were provided on problems that stakeholders have encountered in their interaction with the PLR scheme’s regulations, in particular with the registration process and the way eligible titles are surveyed in New Zealand libraries. The rise of e-books in particular is shown to have implications for the survey methodology currently used for determining eligible library holdings, given that these formats are not included in the survey’s scope nor ‘held’ in the conventional sense (i.e. in a similar way to print-media). E-books are one of a range of technological changes that have occurred in the PLR scheme’s operating environment since it was established in 2008. These include sophisticated digital library and collection management systems, copyright licensing, and e-publishing. Stakeholders emphasised the urgent need to modernise the PLR scheme’s regulations and administration to keep up with these developments and expressed a view that existing collection management software in New Zealand could accurately process holding (and lending) data and automatically calculate PLR scheme payments. An automated system would also reduce administration costs in the long-term.

Stakeholders observed in this context that copyright exceptions under the Marrakesh Treaty relate for the most part to the creation of accessible format copies of a given title that are, for the most part, also digital products. A need was identified to consider the distinction between arrangements that relate to the licensing of digital formats, and the inclusion of digital formats (e.g. digital accessible format copies) of eligible titles in the PLR scheme.

As a first step towards improving the PLR scheme, it has been suggested that New Zealand libraries, their collections and IT managers, copyright licensing organisations, statisticians, and other leading stakeholder organisations combine forces and share their expertise to modernise and streamline how the PLR scheme can achieve desired policy outcomes and best serve New Zealand authors. A revision of the PLR’s governing legislation and regulations may be necessary to deliver to the PLR’s policy intent and keep up with the digital technologies which now define the PLR scheme’s operating environment (Scott & Hartley, 2020, p.1).

Survey responses from librarians

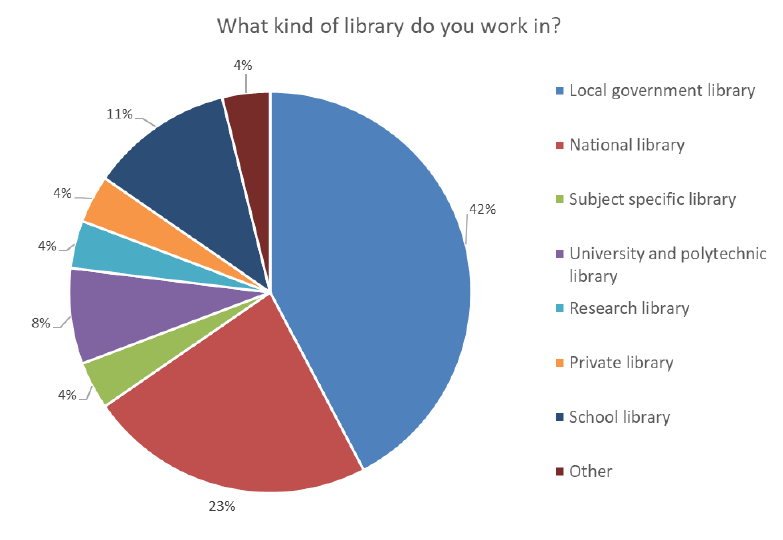

The participating librarians work in a range of types of libraries, as shown in Figure 1. In keeping with the intent of the closed questionnaire for individual stakeholders, the librarians who completed this questionnaire did so as individual professional librarians. The viewpoints of those librarians who indicated that they work at the National Library are their own and not those of the National Library.

More than 75% of the respondents have been librarians for more than 16 years, compared to 12.5% who have been librarians for 6-15 years. The remaining librarians have worked in libraries for 0-5 years.

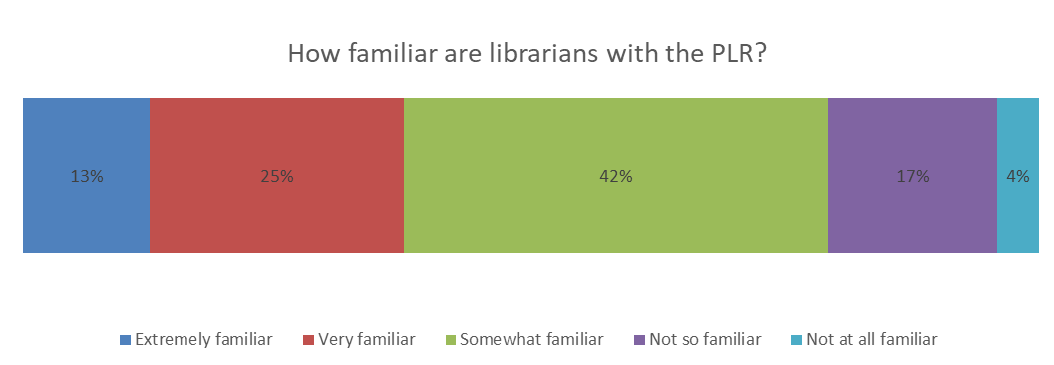

Librarians’ familiarity of the PLR varied greatly between extremely familiar and not familiar at all. More than 40% of librarians were ‘somewhat familiar’ with the PLR. Figure 2 shows how familiar the librarians are with the PLR (Scott & Hartley, 2020, p.6).

The participating librarians work in a range of types of libraries, as shown in Figure 1. In keeping with the intent of the closed questionnaire for individual stakeholders, the librarians who completed this questionnaire did so as individual professional librarians. The viewpoints of those librarians who indicated that they work at the National Library are their own and not those of the National Library.

More than 75% of the respondents have been librarians for more than 16 years, compared to 12.5% who have been librarians for 6-15 years. The remaining librarians have worked in libraries for 0-5 years.

Librarians’ familiarity of the PLR varied greatly between extremely familiar and not familiar at all. More than 40% of librarians were ‘somewhat familiar’ with the PLR. Figure 2 shows how familiar the librarians are with the PLR (Scott & Hartley, 2020, p.6).

School libraries

While the Act defines libraries as “a library that makes its books available for use in New Zealand”, the regulations exclude school libraries. The responses indicated that there is strong support for school libraries to be included in the annual PLR survey. Figures 20 and 21 show that 72% of authors and 62% of librarians support including all school libraries in the PLR. 100% of publishers surveyed support incorporating school libraries into the PLR scheme, or even establishing a parallel Education Lending Right (ELR) scheme, would require a considerable administrative effort considering the sheer number of schools, their individual approaches to acquisitions and their differing cataloguing systems and lending conventions. For these reasons, the inclusion of school libraries in the PLR scheme may be regarded as impractical and prohibitive. LIANZA states that “The catalogues for school libraries are not generally available online so there would have to be consideration given to how to include the data from these libraries in the scheme. School libraries are often not well resourced so LIANZA would not endorse any changes to the scheme that would place an administrative burden on school libraries.” (Scott & Hartley, 2020, p. 24-25).

Private libraries

As with school libraries, private libraries are also excluded from the PLR scheme under the current Regulations. Private libraries are not defined in further detail in the statute. By implication they can be characterised in general terms as representing the opposite of public libraries, that is, as libraries that do not receive any public financial support and are owned by an individual or a group of contributing subscribers or members for their own use. Professional peak bodies and organisations have mixed views as to whether private libraries should be included in the PLR scheme. Waikato District Libraries, LIANZA and Read NZ believe that private libraries should not be included in the PLR scheme.

On the other hand, the NZSA, PANZ, Sandra Morris Illustration Agency and CLNZ agree that private libraries should be included. It is clear from their submissions that they are predominantly thinking of BLVNZ’s library. CLNZ emphasises that the Blind Low Vision library should be included in the PLR scheme: “It [the Blind Low Vision Library] is not only available to the organisation’s visually impaired members. A membership category has been added that, for a fee, provides access to the library's services for people with a print disability. This extends the customer base for the audiobooks in the library, well beyond the small percentage of the population that is visually impaired. As above, this level of free access to authors' work should not come at expense to the author as it currently does. Libraries wishing to avail themselves and their members of the benefits of access to published materials, should be required to provide a dataset of the lending that takes place in their library” (Scott & Hartley, 2020, p.26).

LIANZA believes that including private libraries in the PLR would be difficult to manage, as “they don’t have publicly available catalogues that could be searched for copies of titles" (Scott & Hartley, 2020, p.26).

E-books and audiobooks

LIANZA believe that while it is fair to compensate authors for digital books, “changing the model to include digital lending could have an impact on resourcing for public libraries” and would “increase the cost of administering the scheme and potentially add compliance costs for New Zealand libraries.” LIANZA also argue that an “audit process to verify the results of lending data” would be necessary to validate the payments to authors. (Scott & Hartley, 2020, p.22).

Accessible Format Copies

The Copyright (Marrakesh Treaty Implementation) Amendment Act was introduced in 2020 to help people who are blind, visually impaired or otherwise print disabled to have access to books and literary works in accessible formats. Under the Amendment Act an Authorised Entity may copy works to create an accessible format of a copyright work for the use of someone who has a print disability. In New Zealand copyright law, a ‘print disability’, in relation to a person, is defined as –

a) “an impairment that prevents the person from enjoying a printed copyright work to the same degree as a person who does not have that impairment”, but

b) “excludes an impairment of visual function that can be improved, by the use of corrective lenses, to a level that is normally acceptable for reading without a special level or kind of light.”

LIANZA believes that the issue of authors not receiving payment for the broadened Marrakesh exception could be resolved through any successful solution that is found for incorporating e-books and audiobooks into the PLR scheme: “addressing the issue of inclusion in the scheme for e-books and audio books would largely resolve this impact [of the Marrakesh Treaty] in LIANZA’s view.” (Scott & Hartley, 2020, p28-29)

Opportunities for establishing collaborative partnerships

When the PLR scheme was established in 2008, Parliament excluded digital formats. However, as noted by CLNZ, considerable technological advances during the intervening years in publishing and management systems underscore the need for the PLR scheme to be managed through “an automated data collection and payment system.” CLNZ expects “that, in 2020, manual surveys of holdings should be a thing of the past, and technology should be able to make the process of securing holding and/or lending information, seamless.” By the same token, LIANZA expressed its concern that “any change in process that shifts the responsibility for reporting to a much wider group will invariably increase the resourcing required to administer the scheme as it will require significant communication, education and follow up to ensure the correct information is reported. We note that it would also be likely to need to introduce some kind of audit process to verify the results if individual libraries are being required to report on digital lending for example. Again, this will increase the cost of administering the scheme and potentially add compliance costs for New Zealand Libraries.” (Scott & Hartley, 2020, p31)

During the course of the consultation potential was identified for organisations associated with the PLR scheme and its funding recipients to work together in the PLR scheme’s design. For example, the know-how and connections of the National Library and LIANZA with libraries all around the country could be combined with the technological resources and expertise of Copyright Licensing New Zealand and Statistics New Zealand to streamline aspects of the PLR scheme’s administration – in particular the survey of eligible titles, the collection of e-lending data, and the calculation and distribution of payments. Respondents recommended that the National Library consider utilising existing technologies, rather than trying to reinvent the wheel. Such collaborative partnerships, although they may incur costs to begin with, would bring about greater cost efficiency in the long-term. Furthermore, collaborations between libraries and cultural institutions will uphold the National Library’s strategic aspirations for 2030.

Given the size of New Zealand it would be eminently sensible to create efficiencies by making optimal use of existing collection and library management technologies available to all New Zealand libraries and copyright licensing organisations to automate accurate data collection and payment processes. (Scott & Hartley, 2020, p31)

While the Act defines libraries as “a library that makes its books available for use in New Zealand”, the regulations exclude school libraries. The responses indicated that there is strong support for school libraries to be included in the annual PLR survey. Figures 20 and 21 show that 72% of authors and 62% of librarians support including all school libraries in the PLR. 100% of publishers surveyed support incorporating school libraries into the PLR scheme, or even establishing a parallel Education Lending Right (ELR) scheme, would require a considerable administrative effort considering the sheer number of schools, their individual approaches to acquisitions and their differing cataloguing systems and lending conventions. For these reasons, the inclusion of school libraries in the PLR scheme may be regarded as impractical and prohibitive. LIANZA states that “The catalogues for school libraries are not generally available online so there would have to be consideration given to how to include the data from these libraries in the scheme. School libraries are often not well resourced so LIANZA would not endorse any changes to the scheme that would place an administrative burden on school libraries.” (Scott & Hartley, 2020, p. 24-25).

Private libraries

As with school libraries, private libraries are also excluded from the PLR scheme under the current Regulations. Private libraries are not defined in further detail in the statute. By implication they can be characterised in general terms as representing the opposite of public libraries, that is, as libraries that do not receive any public financial support and are owned by an individual or a group of contributing subscribers or members for their own use. Professional peak bodies and organisations have mixed views as to whether private libraries should be included in the PLR scheme. Waikato District Libraries, LIANZA and Read NZ believe that private libraries should not be included in the PLR scheme.

On the other hand, the NZSA, PANZ, Sandra Morris Illustration Agency and CLNZ agree that private libraries should be included. It is clear from their submissions that they are predominantly thinking of BLVNZ’s library. CLNZ emphasises that the Blind Low Vision library should be included in the PLR scheme: “It [the Blind Low Vision Library] is not only available to the organisation’s visually impaired members. A membership category has been added that, for a fee, provides access to the library's services for people with a print disability. This extends the customer base for the audiobooks in the library, well beyond the small percentage of the population that is visually impaired. As above, this level of free access to authors' work should not come at expense to the author as it currently does. Libraries wishing to avail themselves and their members of the benefits of access to published materials, should be required to provide a dataset of the lending that takes place in their library” (Scott & Hartley, 2020, p.26).

LIANZA believes that including private libraries in the PLR would be difficult to manage, as “they don’t have publicly available catalogues that could be searched for copies of titles" (Scott & Hartley, 2020, p.26).

E-books and audiobooks

LIANZA believe that while it is fair to compensate authors for digital books, “changing the model to include digital lending could have an impact on resourcing for public libraries” and would “increase the cost of administering the scheme and potentially add compliance costs for New Zealand libraries.” LIANZA also argue that an “audit process to verify the results of lending data” would be necessary to validate the payments to authors. (Scott & Hartley, 2020, p.22).

Accessible Format Copies

The Copyright (Marrakesh Treaty Implementation) Amendment Act was introduced in 2020 to help people who are blind, visually impaired or otherwise print disabled to have access to books and literary works in accessible formats. Under the Amendment Act an Authorised Entity may copy works to create an accessible format of a copyright work for the use of someone who has a print disability. In New Zealand copyright law, a ‘print disability’, in relation to a person, is defined as –

a) “an impairment that prevents the person from enjoying a printed copyright work to the same degree as a person who does not have that impairment”, but

b) “excludes an impairment of visual function that can be improved, by the use of corrective lenses, to a level that is normally acceptable for reading without a special level or kind of light.”

LIANZA believes that the issue of authors not receiving payment for the broadened Marrakesh exception could be resolved through any successful solution that is found for incorporating e-books and audiobooks into the PLR scheme: “addressing the issue of inclusion in the scheme for e-books and audio books would largely resolve this impact [of the Marrakesh Treaty] in LIANZA’s view.” (Scott & Hartley, 2020, p28-29)

Opportunities for establishing collaborative partnerships

When the PLR scheme was established in 2008, Parliament excluded digital formats. However, as noted by CLNZ, considerable technological advances during the intervening years in publishing and management systems underscore the need for the PLR scheme to be managed through “an automated data collection and payment system.” CLNZ expects “that, in 2020, manual surveys of holdings should be a thing of the past, and technology should be able to make the process of securing holding and/or lending information, seamless.” By the same token, LIANZA expressed its concern that “any change in process that shifts the responsibility for reporting to a much wider group will invariably increase the resourcing required to administer the scheme as it will require significant communication, education and follow up to ensure the correct information is reported. We note that it would also be likely to need to introduce some kind of audit process to verify the results if individual libraries are being required to report on digital lending for example. Again, this will increase the cost of administering the scheme and potentially add compliance costs for New Zealand Libraries.” (Scott & Hartley, 2020, p31)

During the course of the consultation potential was identified for organisations associated with the PLR scheme and its funding recipients to work together in the PLR scheme’s design. For example, the know-how and connections of the National Library and LIANZA with libraries all around the country could be combined with the technological resources and expertise of Copyright Licensing New Zealand and Statistics New Zealand to streamline aspects of the PLR scheme’s administration – in particular the survey of eligible titles, the collection of e-lending data, and the calculation and distribution of payments. Respondents recommended that the National Library consider utilising existing technologies, rather than trying to reinvent the wheel. Such collaborative partnerships, although they may incur costs to begin with, would bring about greater cost efficiency in the long-term. Furthermore, collaborations between libraries and cultural institutions will uphold the National Library’s strategic aspirations for 2030.

Given the size of New Zealand it would be eminently sensible to create efficiencies by making optimal use of existing collection and library management technologies available to all New Zealand libraries and copyright licensing organisations to automate accurate data collection and payment processes. (Scott & Hartley, 2020, p31)

Helen Heath interviews Alison MacIntyre, Principal Advisor in the Office of the National Librarian

HH: Firstly, thanks for taking the time to explain things a bit further. One thing I was surprised to learn was that e-books were not included in the PLR scheme.

AM: When the bill was introduced to Parliament in 2008, a willingness to consider non-print material in future policy was expressed but compact discs, audio-books and online services were intentionally not included in the scheme. The current regulations are prescriptive and they would need to be changed to allow e-books to be included in the programme. At that time, none of the other jurisdictions included e-books either. I think part of it is to do with the definition of a book in 2008 – and how to define an e-book – is it a file? Is it a transmission or broadcast – what is it? So, I think in 2008 it was just an immature electronic publishing environment.

HH: The other thing I hadn’t been aware of is that school libraries have not been included. Do you know why that is?

AM: There could be lots of reasons. Administratively, it would be really difficult because of the way that our school system is – every single school is an autonomous entity. So, they have their own governance – there is no requirement for a school to even have a library. It depends on each school’s community what the relative value of a library is to them and therefore what they do.

The other thing is that New Zealand is characterised by a lot of small schools, more than half of New Zealand primary schools have fewer than a hundred students. So, the chance of them having a dedicated librarian or even a teacher with library responsibility is slim. If they have an advocate in the community they may have a parent volunteer that feels strongly about it otherwise it is left up to the teachers. The Ministry of Education does not fund school libraries or have any basic requirements around them.

A practical way of including New Zealand books written for the schools market, or for children, was to include the National Libraries Schools Collection in the PLR scheme, because they buy multiple copies of New Zealand works and they distribute those to schools.

HH: I was surprised that, according to the report, many librarians are not aware of how the scheme works. I asked Glen Walker, the LIANZA rep on the Advisory Group and he said that he seriously doubts that almost anyone except authors are very aware of the scheme – or were before the survey shed some light on it.

AM: One of the things that it would be really good to get libraries more involved in is understanding their role in the book publishing landscape and the financial viability of it because that is really what is missing from the story at present.

HH: Something I am working on at the moment is collecting data which demonstrates that borrowing leads to buying – we often hear this anecdotally but need more evidence to show that libraries, authors and publishers are not adversaries.

AM: In terms of New Zealand print runs, the advice from our collectors and content services is that typical New Zealand printing runs (except for the exceptional best-sellers) have a print run of 2,000 or less. If you think of the number of libraries who methodically buy every New Zealand published title that they can, library purchasing probably accounts for a significant amount of sales. We need to make sure that we are not penalising libraries by making it hard for them to support New Zealand authors by buying their books. We need to recognise those relationships – we are all part of the New Zealand publishing ecosystem.

HH: I guess, the more transparent we can be about communicating this the more people will understand that libraries are not the enemy of authors. I suppose it all comes down to government funding?

AM: Anecdotally there are New Zealand authors who deliberately don’t write for the New Zealand audience because it is too small. But I suspect that doesn’t apply to most New Zealand authors.

In some other jurisdictions (particularly the Scandinavian countries and even Canada), there are genres that are included and excluded in their schemes so that the government funding is targeted towards genres that they see are either needing support or incentivising more writing of that type for the wellbeing and benefit of the community. Genres such as poetry, fiction and local voices rather than genres that are less “nationalistic”.

So, we are trying to clarify – what the purpose of the scheme is and what the policy objectives are because at the moment it is really wide open. There is a danger that we can dis-incentivise niche titles, they might not be popular in terms of sales but it takes time and skill to tell the story. Very local stories, poetry, works in te reo probably come under that.

HH: So what’s next?

AM: After the election, there will be an options paper that will go to the Minister (whoever the Minister is). As part of the next stage, for the policy discussion, we are looking at other jurisdictions such as Australia and Canada. They have included e-books and audiobooks in different ways and it will be interesting to hear if it is working the way they expected it to, if it is supporting the policy intent they had in mind when they made those changes.

In 2015, there were roundtable discussions around the literary sector (with authors) and one of the things that came out of that is that there is no feedback loop from libraries to authors about what is loaned and what people are reading and if there are patterns in reading that authors could write for. Libraries have all of that data. Even with book sales data, it is really hard to get an overview of the whole country to analyse. But the lending data is what is really missing – it’s not aggregated anywhere.

HH: Yes, even Nielsen Bookdata, which most authors wouldn’t have full access to, doesn’t cover all book sales in New Zealand.

"Nielsen BookData collects all information on books published around the world into a central database. Librarians, booksellers and publishers are given access to this database on a subscription basis to aid the discovery of titles or to populate their website. It includes New Zealand titles, as well as local details such as New Zealand dollar prices and local distributors for overseas-published titles. Nielsen BookScan monitors sales from chain bookshops, internet booksellers, discount outlets and independent bookshops in New Zealand, and collects actual sales at the point of sale. Nielsen BookScan aggregates the data and provides the book trade with reports, either by direct access to BookScan-Online or through charts.” (Source)

AM: Looking at other jurisdictions, in the socialist countries, particularly when there is a language boundary, such as the Scandinavian countries, they incentivise writing in their local languages. We could do that for te reo. In the British and European models it is included in their copyright law, so authors have the right to stop libraries from holding their books – we’d like to avoid that – although it’s not our decision – but it would be a shame for all of us.

HH: Thanks so much for taking the time to add to the conversation around the PLR Alison. It will be interesting to see how things develop!

AM: When the bill was introduced to Parliament in 2008, a willingness to consider non-print material in future policy was expressed but compact discs, audio-books and online services were intentionally not included in the scheme. The current regulations are prescriptive and they would need to be changed to allow e-books to be included in the programme. At that time, none of the other jurisdictions included e-books either. I think part of it is to do with the definition of a book in 2008 – and how to define an e-book – is it a file? Is it a transmission or broadcast – what is it? So, I think in 2008 it was just an immature electronic publishing environment.

HH: The other thing I hadn’t been aware of is that school libraries have not been included. Do you know why that is?

AM: There could be lots of reasons. Administratively, it would be really difficult because of the way that our school system is – every single school is an autonomous entity. So, they have their own governance – there is no requirement for a school to even have a library. It depends on each school’s community what the relative value of a library is to them and therefore what they do.

The other thing is that New Zealand is characterised by a lot of small schools, more than half of New Zealand primary schools have fewer than a hundred students. So, the chance of them having a dedicated librarian or even a teacher with library responsibility is slim. If they have an advocate in the community they may have a parent volunteer that feels strongly about it otherwise it is left up to the teachers. The Ministry of Education does not fund school libraries or have any basic requirements around them.

A practical way of including New Zealand books written for the schools market, or for children, was to include the National Libraries Schools Collection in the PLR scheme, because they buy multiple copies of New Zealand works and they distribute those to schools.

HH: I was surprised that, according to the report, many librarians are not aware of how the scheme works. I asked Glen Walker, the LIANZA rep on the Advisory Group and he said that he seriously doubts that almost anyone except authors are very aware of the scheme – or were before the survey shed some light on it.

AM: One of the things that it would be really good to get libraries more involved in is understanding their role in the book publishing landscape and the financial viability of it because that is really what is missing from the story at present.

HH: Something I am working on at the moment is collecting data which demonstrates that borrowing leads to buying – we often hear this anecdotally but need more evidence to show that libraries, authors and publishers are not adversaries.

AM: In terms of New Zealand print runs, the advice from our collectors and content services is that typical New Zealand printing runs (except for the exceptional best-sellers) have a print run of 2,000 or less. If you think of the number of libraries who methodically buy every New Zealand published title that they can, library purchasing probably accounts for a significant amount of sales. We need to make sure that we are not penalising libraries by making it hard for them to support New Zealand authors by buying their books. We need to recognise those relationships – we are all part of the New Zealand publishing ecosystem.

HH: I guess, the more transparent we can be about communicating this the more people will understand that libraries are not the enemy of authors. I suppose it all comes down to government funding?

AM: Anecdotally there are New Zealand authors who deliberately don’t write for the New Zealand audience because it is too small. But I suspect that doesn’t apply to most New Zealand authors.

In some other jurisdictions (particularly the Scandinavian countries and even Canada), there are genres that are included and excluded in their schemes so that the government funding is targeted towards genres that they see are either needing support or incentivising more writing of that type for the wellbeing and benefit of the community. Genres such as poetry, fiction and local voices rather than genres that are less “nationalistic”.

So, we are trying to clarify – what the purpose of the scheme is and what the policy objectives are because at the moment it is really wide open. There is a danger that we can dis-incentivise niche titles, they might not be popular in terms of sales but it takes time and skill to tell the story. Very local stories, poetry, works in te reo probably come under that.

HH: So what’s next?

AM: After the election, there will be an options paper that will go to the Minister (whoever the Minister is). As part of the next stage, for the policy discussion, we are looking at other jurisdictions such as Australia and Canada. They have included e-books and audiobooks in different ways and it will be interesting to hear if it is working the way they expected it to, if it is supporting the policy intent they had in mind when they made those changes.

In 2015, there were roundtable discussions around the literary sector (with authors) and one of the things that came out of that is that there is no feedback loop from libraries to authors about what is loaned and what people are reading and if there are patterns in reading that authors could write for. Libraries have all of that data. Even with book sales data, it is really hard to get an overview of the whole country to analyse. But the lending data is what is really missing – it’s not aggregated anywhere.

HH: Yes, even Nielsen Bookdata, which most authors wouldn’t have full access to, doesn’t cover all book sales in New Zealand.

"Nielsen BookData collects all information on books published around the world into a central database. Librarians, booksellers and publishers are given access to this database on a subscription basis to aid the discovery of titles or to populate their website. It includes New Zealand titles, as well as local details such as New Zealand dollar prices and local distributors for overseas-published titles. Nielsen BookScan monitors sales from chain bookshops, internet booksellers, discount outlets and independent bookshops in New Zealand, and collects actual sales at the point of sale. Nielsen BookScan aggregates the data and provides the book trade with reports, either by direct access to BookScan-Online or through charts.” (Source)

AM: Looking at other jurisdictions, in the socialist countries, particularly when there is a language boundary, such as the Scandinavian countries, they incentivise writing in their local languages. We could do that for te reo. In the British and European models it is included in their copyright law, so authors have the right to stop libraries from holding their books – we’d like to avoid that – although it’s not our decision – but it would be a shame for all of us.

HH: Thanks so much for taking the time to add to the conversation around the PLR Alison. It will be interesting to see how things develop!